If

you enter Holyrood Park from Meadowbank Terrace and walk a short way along

Duke’s Walk, you may notice a pile of rocks that appear to have been

abandoned. However, on closer

examination you will find that this is a low cairn, roughly cemented together. Like me, on first seeing it you may think

‘What the **** is that about?’ Well, it

turns out that it is a cairn laid in the memory of a victim of a horrible

murder that took place in the park in 1720.

Muschet’s

Cairn, on the gentle slope of a grassy mound in Holyrood Park

Muschet’s

Cairn in Holyrood Park

Muschet’s

Cairn by Duke’s Walk, Holyrood Park

One

of the main characters in the story behind the cairn is a rather pathetic

individual called Nicol Muschet. Nicol

was the eldest of several children and was brought up in an extremely religious

and God fearing, Presbyterian household, at the family estate in Boghall. His father died when he was young and after

this Nicol became a bit of a mollycoddled mummy’s boy, who made a show of being

pious and holy to please his mother.

As

a young man, Nicol left the clutches of his mother and went to Edinburgh where

he studied at the university there to become a surgeon. Like many young students leaving home for the

first time, Nicol soon discovered the joys of bad company, drunkenness, and

sex. After graduating as a surgeon in

1716, Nicol moved to Alloa and became an apprentice to the surgeon John

Napier. However, he found that Napier

had little work for him and his life in Alloa was very dull compared to the

life he had lived in Edinburgh. So, after a year or so Nicol left Alloa and

returned back home to his mother, thinking that living the life of a country

Laird could be to his liking. There

though, he soon found that he had no aptitude for managing the estate and his

mother’s piety and the way she expected him to live his life irritated him

greatly. It was not long before he was

looking for something else to do.

In

August 1719 Nicol took a trip to Edinburgh to watch a dissection take place at

the university. He took some temporary

lodgings with a view to maybe staying on and finding work in the town as a surgeon. A few days after arriving he was out walking

when he passed the house belonging to Adam Hall, a merchant of the town. Standing outside was the maid of the house

and Nicol recognised her as an acquaintance from his days as a student. He stopped to chat with her, and she invited

him into the house for a drop of ale.

They had a drink together and caught up with what was happening in each

other’s lives. While they were sitting

talking, they were joined by Margaret Hall, the daughter of the house. Nicol’s friend then left to carry out her

chores, leaving Nicol and Margaret in each other’s company. As they talked, Nicol found that not only was

Margaret attractive, but she was easy company to keep, young, impressionable,

and already bit infatuated with him. He

decided that it may be fun to try and seduce her. This little plan was helped along by Margaret

finding him more permanent lodgings with a friend of her family. She then became a regular visitor and spent

much time with him.

On

the 5 September 1719, after knowing each other for just three weeks, Nicol and

Margaret were married. Nicol’s plan to

seduce Margaret had worked, but unfortunately for him her father had found out

and demanded for the sake of his daughter’s honour that they marry. So, marry they did. Now, Nicol could have been happy with his

lot, as not only did he now have a young and attractive wife, he had also

married the daughter of a wealthy merchant.

And maybe for the first few weeks Nicol was happy, but he soon grew

bored of Margaret and with his boredom grew a resentment of her. He began to blame her for trapping him in a

marriage he did not want and saw her as some floozy who had seduced him. He was one of those weak men who always

blames others for their misfortunes, rather than admitting to any mistakes they

may have made. Who convince themselves

that they have been wronged rather than seeing the faults in any of their own

actions. So, after being married for a

couple of months Nicol decided to leave his wife and travel out of Scotland to

seek work as a surgeon.

Nicol

left Margaret at her father’s house on Castle Hill, where they had been living

together, and made his way back to his mother’s. There he gave her a story about wanting to

travel abroad to better his career as a surgeon and asked her for the money to

do so. It would appear that Nicol did

not let his mother know anything of his marriage to Margaret when discussing

his plans for a life abroad. Indeed, his

mother seems to have known nothing of his marriage until many months later. Nicol’s plans for his future did not go down

well with his mother, who was worried that it exposed her son to a dangerous

life in foreign lands. Given this she persuaded

him not to pursue this idea any further.

Disillusioned

and angry and feeling that his mother had thwarted his plans, Nicol returned to

Edinburgh a few days later. He did not,

however, inform Margaret of his return and rather than returning to her

father’s house, he lodged in the rooms of a friend. While back in Edinburgh Nicol met up with

James Campbell of Burnbank, or Bankie to his friends, an acquaintance with whom

he had some business transactions.

Bankie was the Storekeeper at Edinburgh Castle and was by all accounts a

devious and cunning individual and as corrupt as they come. Nicol told Bankie of his woes and after

listening to him, Bankie said that he could help…for a sum of money of course. He told Nicol that for the sum of £50, he

would arrange for Margaret’s name to be so besmirched that Nicol would have no

problem in being granted a divorce from her.

Over a few ales at a nearby tavern they then drew up an agreement in

which it was stated that Nicol would pay Bankie the money on him producing

‘…two legal depositions, or affidavits of two witnesses, of the whorish

practices of Margaret Hall…’

Over the

next few days in taverns around Edinburgh, Nicol and Bankie met up to discuss

their plot against Margaret. Bankie then

came up with the idea that Nicol would take up rooms in a nearby tavern and

they would both meet up with Margaret for a drink there. They would then drug her by lacing her drink

with liquid laudanum so that she would fall asleep. Once asleep they would undress her and put

her to bed, then a friend of Bankie’s, John McGregory, would lie naked in the

bed with her. Two other friends of

Bankie, James Muschet (a distant relative of Nicol’s) and his wife Grissel Bell

would be called from a nearby tavern to witness this. They would then provide the evidence for the

claims of adultery against Margaret.

Nicol and

Bankie looked around for a suitable place in which to carry out their plot and

soon found rooms in one of the many taverns in Edinburgh. A few days later they invited Margaret around

for a drink. By this time Nicol had told

another of his friends, Alexander Pennecuik, about the plot and had persuaded

him to help. So, Margaret came round to

the tavern and Nicol made his excuses to her for his previous behaviour and

entertained her while Bankie and Pennecuik provided her with drinks they had

spiked. Margaret became sleepy after a

while but did not pass out. Getting

bored of waiting, Nicol took her up to bed and lay with her for a while until

she fell asleep. He then jumped out of bed and left the room while McGregory,

who had been waiting in the wings, stripped naked and jumped in. The witnesses were then called in to view the

scene and McGregory got out of the bed and left.

While

Margaret slept, Nicol and his co-conspirators left the tavern. Nicol went to his friend Pennecuik’s rooms in

the Canongate. There he wrote a letter

to Margaret telling her that he had left her because of her adulterous

behaviour, was on his way to London and she would never see him again. He had the letter delivered to her and stayed

hidden with Pennecuik for the next two weeks.

Nicol appears to have believed that his letter would put Margaret into

such a state of despair that she would jump into bed with the first man going and

he would then have plenty of evidence of her adultery. However, on receiving the letter Margaret’s

first thoughts were that she must go to see Nicol’s mother to plead her case

and let her know that she was innocent of the accusations made against

her. Before leaving Edinburgh for the

journey to Boghall, Margaret bumped into Bankie and told him of her plans. He tried to persuade her not to go and told

her he would trace Nicol for her, but she left later that day anyway. Worried that she would scupper his plans and

win an ally in Nicol’s mother, Bankie gave false evidence to a Justice that Margaret

was suspected of theft and obtained a warrant for her arrest. He and an associate then set of in pursuit of

her and caught up with her in Linlithgow.

There they arranged for her to be arrested by a local Constable. After she was arrested Bankie turned up and

pretended to be a concerned friend who had heard of her trouble. He told her that he had arranged for her to

be bailed, but she would have to come back to Edinburgh with him for this to be

done. In Edinburgh Bankie arranged and

paid for accommodation for her under the pretence of looking after her while he

sorted out her bail. In reality though

it was to keep her away from friends and family, who may become suspicious of

him if she told them what had happened.

After a couple of days in Edinburgh, Margaret decided once again to

leave. She hired a horse and discreetly

left, travelling down to Boghall before Bankie was aware she had gone. Bankie, still plotting away as ever, then

wrote her a long letter promising her that if she returned to Edinburgh, he

would plead her case with Nicol and let him know that everything had been a

misunderstanding. Margaret, still in

love with Nicol and believing that her marriage to him could still be salvaged,

returned.

Realising

that Margaret was not going to do them the favour of finding herself another

man, Nicol and Bankie took the evidence they had manufactured against her to a

lawyer they were friendly with. He

looked through what they had and advised them that unless they could show that

McGregory and Margaret knew each other and had been seen several times in each

other’s company, they had no case.

Disappointed with this outcome they made their way to a nearby tavern to

plot what to do next. There they came up

with the great idea that Bankie would invite James Muschet, his wife Grissel

Bell, Margaret and McGregory to his rooms for drinks. If this were done for several days, Margaret

would have then been seen in McGregory’s company enough times for them to

proceed with their case against her.

Nicol would, of course, pay McGregory, Muschet and Bell to attend and

would also pay for their drinks. The plot

was put into action, but very quickly Nicol grew disillusioned with it, as it

seemed he was just paying out a lot of money for Bankie and his associates to get

drunk. So, he called it all off and gave

up on the idea of divorce.

Shortly

after this Bankie and Nicol came up with another idea. Murder.

They would poison Margaret. She

had happily taken the drinks spiked with Laudanum, so why not put poison in her

drink and be done with her for good?

They decided that James Muschet would be the man to do it and that Nicol

would pay him for poisoning her and would also provide the poison

required. So, James Muschet was provided

with a paper of sugar and poison and some brandy. He took this to Margaret and drank with her,

adding the poisoned sugar to her drink. However,

rather than killing her, the poison made Margaret violently ill and vomit for

several days, but then she recovered.

Bankie,

not disheartened by this told Nicol that they should just keep on poisoning

her, as it would weaken her and eventually kill her. Nicol agreed with this, and they decided that

they would change from the poison they had been using and instead use corrosive

mercury. To keep Margaret from becoming

suspicious this was added to nutmeg in a nutmeg grater, as Margaret would grate

this herself into her ale. Again, this

did not work and though it made Margaret ill she stubbornly didn’t die. However, it was noticed that the poison had a

devastating effect on the nutmeg grinder, which was discoloured and looked like

it had been burnt. It was discreetly

removed and given to Alexander Pennecuik to dispose of. Nicol, who had not seen Margaret since he had

supposedly left for London, then decided to pay her a visit, and help things

along. He went to Margaret’s lodgings

and on the pretence of making amends, spent time with her, drank with her and

provided her with drinks. The drinks

were of course poisoned with corrosive mercury.

James Muschet, who was there too, poisoned a few of her drinks as

well. Apart from making her ill, the

poison had no other effect. Nicol

decided that this plot was going nowhere, and it was dropped

In one of

the many taverns in Edinburgh the plotters met again to discuss their plans on

how to get rid of Margaret. Bankie

suggested that James Muschet could invite her to Leith, get her drunk and then

drown her in a pond on the way home.

James did not like this idea, as he felt it would be too obviously a

murder and that he would end up being hanged for it if they went ahead. Grissel suggested that she and James ride out

with Margaret and that the saddle on her horse could be loosened so that it

would throw her. If they arranged this near

to Kirkliston Water, she would be drowned, and it would look like an accident. It was decided that there were too many

difficulties in arranging this. The plan

they eventually settled on was that Grissel would invite Margaret to her and

James’ rooms in Dickson’s Close and she would entertain her and keep her there until

late in the night. James meanwhile would

hide out in the close and strike Margaret over the head with a hammer when she

left to make her way home. He would then

arrange her body, so it looked like she had fallen in the dark and struck her

head. Did this plot succeed? Of course not. Several attempts were made. Margaret went to visit Grissel and stayed

late, but every time she left there were people around in the street, so James

was unable to strike her. The plan then

had to be put on hold for a week, as James had developed severe toothache from

standing out in the cold waiting for Margaret to leave. Then when he was better, their landlord grew

annoyed by Margaret staying late all the time and told James and Grissel she

was not welcome there anymore.

Nicol was

now completely fed up with the plots and felt he had been duped by Bankie,

James and Grissel. He wondered if they

had ever had any intention of carrying through with any of the plots or if they

were just stringing him along to get money out of him. He realised that if he wanted to be rid of

Margaret, he would have to take matters into his own hands.

On the

morning of Monday 17 October 1720 Nicol borrowed his landlady’s knife and then

spent some time in the Canongate Kirk listening to sermons. On leaving the kirk he made his way to

Barnaby Lloyds, a nearby tavern. There

he met James Muschet and again they hatched a plot to kill Margaret. This time it was agreed that James would hide

in a nearby close, and that Nicol would leave the tavern with Margaret, lead

her down the close and James would strike.

Margaret was then sent for, and she arrived and spent time drinking with

the two men. James then left to go and

take his place in the close and wait for them.

Once he had left Nicol realised that it was unlikely that James would

carry through with this latest plot and he was overtaken with a desire to kill Margaret

himself, as that way he could get it over and done with. He asked her to walk with him to Duddingston

and she agreed to accompany him there. As

they walked, Margaret became increasingly aware of Nicol’s silence and his strange

mood. Tired and fed up with the way he

treated her and never being quite sure of his feelings towards her, she asked if

he would rather she just left him to his thoughts and went home. Nicol grew angry with her, and he told her

that if she left him and returned home, he would have nothing more to do with

her. Margaret then carried on walking

with him. They reached Duke’s Walk in Holyrood

Park and there Margaret questioned the route they were taking. Nicol told her they were taking a different

route to Duddingston, then made as if he was going to embrace her and put his

knife to her throat. Margaret cried out to

him – ‘And was that your design in bringing me here, to cut my throat?’ Nicol then accused her of being a whore and

cheating on him. Margaret, who was

innocent of all the accusations he made, denied them saying she had done

nothing wrong other than loving him. He

then made to cut her throat with the knife, but she moved her head defensively

and he caught her on the chin. She then

fought with him and tried to grab the knife from him, but he cut through her

hand with it. She cried to him – ‘My

love, my love, do not murder me.’ Nicol

had no time for her cries for mercy and in his cold rage he grabbed her by the

hair, pulled her to the ground and cut her throat several times with the

knife. As Margaret lay on the ground

dying, she said to him - ‘Oh man! It is

done now, you need not give me more.’

Nicol then walked away from her, but suddenly fearing she that might

recover from the wounds he had inflicted he walked back to where she lay and

‘cut her throat almost through, and so left her.’ He then fled the scene and went to James

Muschet’s rooms where he told James and Grissel what he had done.

The next

morning Margaret’s body was found and by her body was the sleeve of a man with

the letter N embroidered in green silk on it.

The body was identified later that day as being that of Margaret Hall and

it was quickly realised that the sleeve must belong to her husband Nicol. Grissel, in the meantime, had come to the

conclusion that it may be best for her and James to get their side of the story

out before Nicol was arrested, so she went to the authorities and told them

what she knew of the murder and of Nicol’s confession to her. She and James then gave ‘King’s evidence’

against Nicol and in return were spared from any prosecution. A few days later Nicol was arrested and

confessed to the murder. In prison as he

awaited trial, Nicol received a letter from his mother, Jean Mushet. In this she told him how ashamed she was of

him and of the terrible acts he had committed.

She advised him to put aside any thoughts of escaping justice and that

he should accept his guilt and the sentence handed to him by the court. He should repent, as without evidence of true

sorrow and repentance for his crimes, his soul was heading to a ‘burning lake

of fire and brimstone’.

On 5

December 1720 Nicol appeared at court in Edinburgh, where he acknowledged that

he had murdered his wife and was then found guilty of her murder. He appeared again at court on 8 December 1720

for sentencing and was sentenced to death.

The Judge ordered that he be taken to the Grassmarket on 6 January 1721

and there, between the hours of two and four in the afternoon, be hanged until

dead. Given the heinous nature of his

crime and the innocence of the victim, his body was then to be hung in chains on

the Gallow Lee, between Edinburgh and Leith.

While in

prison awaiting execution, Nicol wrote an account of his life and the events

leading up to the murder of Margaret. He

tried to excuse many of his actions and stated he had been led astray by

Bankie, James Muschet and Grissel Bell.

He also denied rumours that he was a drunk, had attempted suicide on

various occasions and had been having an affair with his landlady, Mrs Macadam. Rumours that we can imagine were all probably

true. The day before he was to be

executed Nicol received a letter from Alexander Pennecuik. In this letter Pennecuik asked that his name be

cleared, and that Nicol should admit to the lies he had told about his, Pennecuik’s,

involvement in the plot against Margaret.

Nicol replied that everything he had said to the authorities about

Pennecuik was true and that he knew this.

On the

afternoon of 6 January 1721 Nicol was taken from his cell at the Tolbooth by

the City Guard and travelled the short distance down to the Grassmarket, where he

no doubt drank a few ales and brandies before being led to the gallows. There, in front of the crowd gathered to see

the monster who had so cruelly and brutally murdered his young wife, he was

hanged. His body was then cut down and wrapped

in chains and taken to the Gallow Lee.

There it was hung up for all to see, to be pecked by birds and to decay

and crumble. And that was the fate of

Nicol Muschet, a drunk, a fool and a cruel, violent man who married in haste

and then, regretting the marriage, brutally murdered his wife.

There is

a rather macabre tale about Nicol Muschet’s body as it was rotting in its

chains. A butcher called Nicol Brown was

drinking in a tavern one night with a group of his fellow butchers. As the drink flowed, they got into a dispute

about how long meat could be kept before it was cooked and eaten. As more drink flowed, they began to place

bets and Brown bet them a guinea that he could eat a pound of the oldest, most

rotten meat they could find. The bet was

taken and some of the group went off to find the most disgusting hunk of meat they

could. As they walked through the town

discussing where to get this foul flesh from, one of them remembered that Nicol

Muschet was hanging in chains at Gallow Lee.

So, they procured a ladder and some other implements and went down to

the gallows. There they cut a hunk of

flesh from his rotting corpse and took it back to present to Brown. Brown, who was not one to lose a bet, cooked

the flesh like he was cooking a beefsteak and then with the aid of much ale and

whisky he ate it all and won his guinea.

So, what

of Bankie’s fate? Well, Bankie, unlike

James Muschet and Grissel Bell, did not escape justice. He appeared in court in March 1721 charged

with the various attempts made on Margaret Hall’s life. He was found guilty and was banished for life

to ‘His Majesty’s Plantations in America.

The local

populace of the Abbeyhill area of Edinburgh, where the murder of Margaret had

taken place, were so shocked by what had happened that they built a cairn to

mark their horror and to remember her.

The original Muschet’s Cairn stood a short distance to the west of where

the present cairn now stands. It was

moved in 1823 when a footpath was constructed through the park.

I left a

Skulferatu at the cairn.

Skulferatu

#40

Skulferatu

#40 amongst rocks of Muschet’s Cairn

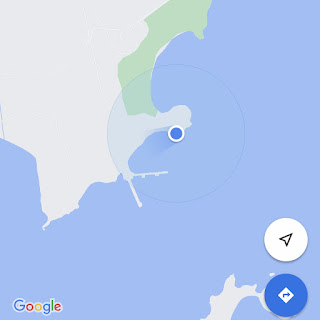

Map showing

location of Skulferatu #40

The

coordinates for the location of the Skulferatu are –

Latitude 55.954470

Longitude

-3.158299

I

used the following sources for the tale of Muschet’s Cairn –

The Confession, & c. of Nicol Muschet, of Boghall, who

was executed in the Grassmarket, January 1721 for the Murder of his Wife, in

the Duke’s Walk, near Edinburgh.

Printed for Oliver and Boyd; Wm. Turnbull, Glasgow; and Law

& Whittaker, London.

1818

Criminal Trials illustrative of the tale entitled The Heart

of Midlothian, Published from the Original Record

Edited by Charles Kirkpatrick Sharp

Edinburgh

1818

Nothing but Murder

By William Roughead

Sheridan House

New York

1946

Book of Scottish Story

Traditions of the Old Tolbooth of Edinburgh

By Robert Chambers

1896

Available at –

Book of

Scottish Story - Historical, Humorous, Legendary, Imaginative

(electricscotland.com)

Article

and photographs are copyright of © Kevin Nosferatu, unless otherwise specified.