I

only discovered the joys of the walk out to and around Cramond Island during

lockdown. It was one of these places

that I had always meant to go to though never quite got round to doing it. I had cycled and walked along the front at

Cramond and passed the causeway out to the island many times but had just never

ventured out there. One of the few joys

of lockdown though was discovering new places to walk and making a point of

actually going to places in my locale.

So, for maybe the third time in a year I went on a stroll out there

today. Before setting out I checked the

tide times, crucial to avoid getting trapped on the island and wasting the time

of the local Lifeboat crew. I then took

a stroll along the causeway to the island.

The

causeway out to Cramond Island is a rough concrete path, raised a few feet up

from the sand. It is covered in cockles,

and I found myself dancing around the path trying not to squash them. Running along the side of the causeway is a

very distinctive looking barrier of concrete pylons, this was built in WWII as

an anti-boat barrier.

Causeway

out to Cramond Island

Concrete

Pylons built in WWII as an anti-boat barrier

Gun

emplacement at the South Side of Cramond Island, by the Causeway

Gun

emplacement at the South Side of Cramond Island

View

over to Granton and Arthur’s Seat from Cramond Island

On

the island there is a path that takes you all the way around, past a host of

abandoned concrete and brick buildings.

These are the remains of the fortifications that were built here during

WWII and are the buildings that housed various gun emplacements and

anti-shipping searchlights. On one of

the beaches are two huge concrete blocks, these were anchor points for an

anti-submarine net that stretched over to Inchcolm Island and then over to the

Fife coast.

Abandoned

WWII building on the island

Inside

view of one of the abandoned WWII buildings

Abandoned

WWII buildings on the island

Abandoned

WWII buildings on the island

View over

the Forth to Fife from one of the buildings

Bunker

at north side of the island

Bunkers

at north side of the island

Abandoned

WWII building on north side of island

Ruined

building and rusting doors

Concrete

blocks on beach that were anchor points for an anti-submarine net

Detail

of one of the concrete blocks

The

WWII buildings left on Cramond Island pale in comparison to those that can be seen

on the island of Inchmickery which sits between Cramond Island and the Fife

Coast. The island there is so covered in

the concrete remains of WWI and WWII fortifications that it looks like a large

battleship sitting out in the Forth. At

one point in time Inchmickery was famed for its oyster beds and the ‘rich profusion

of sea-weed, mosses and lichens, on its beach and surface.’ Now these have pretty much all disappeared.

Inchmickery

Island

Cramond

Island has a history stretching back into the mists of time. It is believed that the Romans would have

used the island during their time in Cramond, however no archaeological

evidence of this has been found.

View out

over the causeway from top of hill on Cramond Island

In

1596 the island was the site of a duel which ended a long running feud. The feud came about after Mary Queen of Scots

had fled to England leaving behind various factions in Scotland who were

hostile to each other. Some supported

the Queen, while others supported James Stewart, the Earl of Moray, who was

acting as the Regent. One of those who

supported the Queen was Stephen Bruntfield, the Laird of Craighouse, while one

of those who supported the Regent was Robert Moubray, Laird of Barnbougle and

an arch enemy of Bruntfield. In 1572, Moubray,

who was hoping to ingratiate himself with the Regent, lay siege to Bruntfield’s

castle at Craighouse. Bruntfield held out

for a while but surrendered to Moubray when he was promised by the Regent that

his life would be spared, and he would keep his property and estates. Moubray however saw Bruntfield’s surrender as

a perfect opportunity to get rid of someone he despised, and while escorting

him to Edinburgh, to meet with the Regent, he ran him through with his sword

and murdered him. Bruntfield’s widow was

so overcome with grief at the death of her husband that she retired to her

rooms within Craighouse Castle, draped them in black and never left them

again. According to those who knew her,

she then spoke of nothing but having revenge on Moubray for the murder of her

husband. This obsession with revenge

she passed on to each of her three sons who each took a turn in duelling with

Moubray. The eldest, Stephen, was the

first to try his hand and Moubray slew him at a duel just outside Holyrood

Palace. A couple of years later, her

middle son, Roger, fought a duel with Moubray and seemed to be gaining the

upper hand, but he slipped and fell and Moubray struck off his head as he lay

on the ground. A few years after this,

the youngest son, Henry, also challenged Moubray to a duel. There was some debate about whether a duel

could be fought given that Moubray had already fought twice over the same issue,

but as Moubray was keen to fight again it was agreed that the duel could go

ahead. On Cramond Island, a spot was

chosen close to the northern beach with a raised area behind it where

spectators could gather. The duel then

took place, and it was bloody and long with both duellists seriously wounding

each other. Eventually as both were

stumbling with fatigue Henry found a last reserve of strength, lunged with his

dagger drawn at Moubray and stabbed him through the heart. Moubray gave a sigh of surprise at having

lost and fell down dead. Henry’s mother,

on hearing the news that Moubray had been killed and she had been revenged,

promptly dropped down dead as well.

Henry then later married Moubray’s niece and inherited much of Moubray’s

wealth and property.

Cramond

Island has also been the scene of many tragedies involving ships coming to

grief on the rocks around it, or people being drowned when caught by the tide

while making the crossing to and from the island. In 1954 a Gunner who was stationed on the

island, drowned while making his way back after a day’s leave. The incoming tide caught him as he tried to

wade out to the island and his body was found the next day lying in a rock

pool.

For

many years, the island was used for farming and grazing sheep. Though now uninhabited, up until the 1930s people

lived on the island, and an article in the West Lothian Courier of 1923

describes it as being the only inhabited island in the Forth. It goes on to describe there being ‘several

small red-tiled cottages upon the island.

In the most sheltered corner they lie, and were built, it is said, out

of the remains of a large house which used to stand there.’

It

was rumoured that there was an underground passage on the island that led, get

this for a nice and vague description, ‘somewhere’. This secret passage was described as having

been lost for centuries and it is probably no surprise to hear that no trace of

this has ever been found.

The

island was also one of the favourite haunts of the author Robert Louis

Stevenson and in his youth he and one of his friends would regularly canoe from

Granton out to Cramond Island.

Cramond

Island has also been the site of the DIY ‘Island of Punk’ festival. The festival lasts for a day with the

audience helping the bands to carry their equipment across the causeway to the

island. Various punk bands have played

there including local Edinburgh favourites such as Oi Polloi and Bloco Vomit.

On

my trek today around the island I left the Skulferatu that accompanied me in

the ruined wall of the Duck House, a building that was once a shelter for

shooting parties and later rented out as holiday accommodation. Now it is little more than a wall facing out

to the Forth Bridges.

Remains

of the Duck House

Skulferatu

#37

Skulferatu

#37 in crack in wall at the Duck House

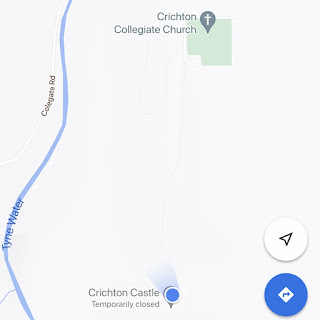

Map

showing location of Skulferatu #37

The

coordinates for the location of the Skulferatu are –

Latitude 55.994815

Longitude

-3.291634

I used the following sources for information on

Cramond Island -

Cassels Old and New Edinburgh,

Vol 3

By James Grant

1883

The Book of Scottish Story

Various Authors

1896

The Scotsman 4th

June 1925

Favourite Haunts

of R.L.S.

West Lothian

Courier – Friday, August 3, 1923

Cramond Island –

An Appreciation

Belfast Telegraph – Monday,

August 16, 1954

Wikipedia

Wikipedia - Cramond

Island

Article

and photographs are copyright of © Kevin Nosferatu, unless otherwise specified.