On a sunny, but very windy day, I took

the train out to Aberdour and then walked along the Fife Coastal Path towards

Dalgety Bay. The path wound its way

through woods where birds chirped, insects buzzed, and everything swayed

slightly in the stiff breeze. The path then

led me through a field, where I ended up by Braefoot Terminal. A rather charming looking area of high fences

and security where liquefied petroleum gas is stored and pumped out into the large

tankers that dock there. Following a

path by one of the security fences I made my way into Braefoot Plantation,

where the remains of Braefoot Battery lie.

Braefoot Battery was a First World War

coastal defence site that overlooked the Firth of Forth. In early 1914, just shortly before the start

of the war, the government bought the land the battery now sits on from the

Earl of Moray. It would seem however,

that there had been plans for quite some time to build a battery there in

preparation for any attack by enemy forces on the UK. Construction then began with the battery

being completed in 1915. When finished

it had two 9.2 inch guns, which could fire a shell weighing 55kg a distance of

up to 26KM. These large calibre guns were

intended for use on enemy ships that may come into the Forth to attack either ships

anchored there or the naval base at Rosyth.

In 1917 the defence of the Forth was

restructured and the guns at the Braefoot Battery were no longer needed

there. They were dismounted and put into

storage, with one gun later being sent to Portsmouth. The site was again used in WWII and several

new buildings were added.

A post war woodland plantation now grows

all around the battery buildings and though this gave my walk a lovely woodland

feel, the trees did obscure what once must have been quite spectacular views

from the hill the battery is on.

After walking around the woods, I made my

way down to the nearby shore. Like almost

everywhere along the coast of the Forth, probably the whole coast of Britain,

there is a rather tragic story connected to this place. A tale so horribly tragic that I just have to

tell it...

...in 1887, on a sunny afternoon in

mid-May, James Turnbull, a solicitor who lived in Aberdour, decided it would the

perfect sort of day to sail out in his boat.

The perfect sort of day to get a good view of the construction work

going on in the building of the Forth Bridge.

So, he invited his chief clerk, a Mr Ramsay, to comer along with him on

this little jaunt. The two men set sail and

the weather was quite lovely, just until they got to Braefoot Point where a

sudden squall caught them. The small

boat they were in was not built for these sorts of choppy waters and high waves,

and it soon filled with water and began to sink. The two men, both of whom were unable to

swim, stood on the deck of the boat as the water first reached up around their

ankles, and then up around their waists.

But behold, a passing steamer.

The two men on seeing the ship waved and shouted at it, hoping to be

rescued. On the deck of the steamer, the

passengers thought they were seeing two bathers in the water waving as they

went past. So, they waved back, and the

ship steamed on. As the water reached up

to their necks, both Turnbull and Ramsay realised they were doomed. They said a little prayer, then their

goodbyes to each other before the sea swallowed them up. Now, on the steamer it so happened that three

of the passengers who had been waving to the doomed men were none other than

Turnbull’s daughters. On their arrival home

they excitedly chattered to their mother about their trip on the ship and

having seen some bathers at Braefoot Point.

A friend of Turnbull’s was waiting in the house to see him and realising

that he was not the most accomplished of sailors, had become concerned about

how long it was taking for him to return.

On hearing the girls talk he had a sudden horrible realisation of what

they might have in fact seen. He quickly

summoned some men, and they made their way to Braefoot Point. There they found Turnbull’s boat washed up on

the shore. Shortly afterwards, as the

tide went out, they found the bodies of both Turnbull and Ramsay. Two

men who quite literally had been not waving but drowning.

On the shore at Braefoot Point there

stands an old pier. I made my way out

onto it and the wind, which had been getting up all day, battered me this way

and that, making it difficult to even keep my balance. The sea was rough, being whipped up by the

wind and I understood how it could easily overwhelm a small boat like that which

Turnbull and Ramsay had been sailing. Feeling

decidedly unsafe, despite being on dry land, I quickly made my way back and

walked over to one of the battery pill boxes, which stood out on the rocks overlooking the Forth.

There, in a howling gale, I left the

Skulferatu that had accompanied me on my walk in a hole in the wall.

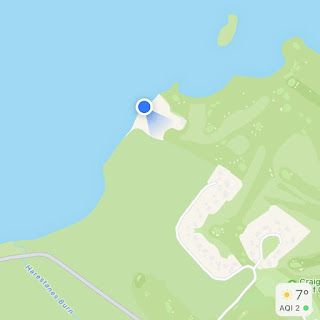

The coordinates for the location of the

Skulferatu are –

Latitude 56.034242

Longitude -3.321253

what3words: throat.points.loved

I used the following sources for

information on Braefoot Battery and Braefoot Point –

Dundee Courier -

Saturday 14 May 1887

Manchester Courier and

Lancashire General Advertiser - Monday 20 April 1914

Canmore

Canmore - Forth

Defences, Middle, Braefoot Point Battery

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)