In

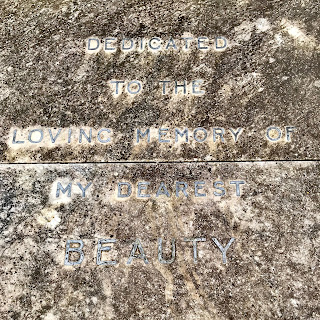

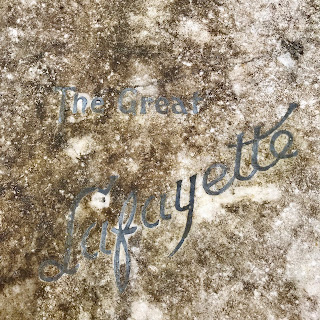

a rather non-descript and suburban Edinburgh cemetery there is buried a

legendary entertainer, magician, and illusionist from a bygone era. A man, who back at the start of the 20th

Century, was one of the most sought after acts in both the USA and the Europe. The grave is that of the Great Lafayette, and

also his pet dog, Beauty. Today I took a stroll in the howling wind through the

backstreets of Leith, Restalrig, Lochend and Piershill to pay them both a

visit.

The

Great Lafayette, whose real name was Sigmund Neuberger, was born on February

25th, 1871 in Munich, Germany. In 1890, when aged 19, he and his family

emigrated to the USA. There he worked

for a while as a bank clerk, but always had an interest in the music hall and

the theatre. He started out as an

amateur with an act that involved shooting with a bow and arrows. The sort of act where he would shoot a coin

out of someone’s fingers. As time went

on, he decided he wanted to try his luck in the entertainment industry and left

home with £80 of his hard earned savings.

His parents couldn’t understand why he had left a good job at the bank

to pursue such a financially insecure career and told him that he would soon

return home penniless. However, within

weeks of leaving he had secured an engagement at Spokane Falls,

Washington. From there his career

developed and he became renowned for an act that included quick costume

changes, magic and elaborate illusions involving a troupe of actors, acrobats

and animals. He also sang, danced,

played various instruments, and composed the music for his shows. The Great Lafayette, as he was then known,

became much in demand and was soon touring the world. He commanded large fees for his act and was one

of the highest paid stars of that era.

It was reckoned that he was earning around $44,000.00 a year, which in

today’s money would be over three and a half million dollars.

One

of his more elaborate acts, that soon became a favourite with audiences

worldwide, was ‘The Lion’s Bride’. This

act, which involved a real, live lion in a cage, now seems a bit dated, cruel and

full of racial stereotypes. It is

basically the story of a beautiful maiden who is shipwrecked in the Persian

Gulf and then captured by the servants of the tyrannical monarch there, Alep

Arslan. Arslan is entranced by the

maiden’s beauty and wants her for his harem.

However, the maiden rejects his advances, much to his annoyance. Her lover, played by the Great Lafayette,

attempts to rescue her, but she ends up back in the clutches of Arslan. She is then offered the choice of becoming Arslan’s

wife or being thrown into a cage with a ferocious lion. She chooses to die,

rather than give herself to him. Arslan has her placed in a cage with a real

lion and in the finale of the act, which thrilled audiences, the lion would

leap towards her, only for the Great Lafayette to burst out of it revealing it

was actually him in a lion costume. The

real lion having been switched when a group of fire-eaters, jugglers and

performers obscured the audience’s view of the cage.

While

he was touring The Great Lafayette was given the gift of a pet dog by his

friend Harry Houdini. He named the dog

Beauty and soon doted on her. She went

everywhere with him and became part of his act.

He spoiled the dog rotten and treated her as his best friend, buying her

a diamond studded collar and giving her, her own room, in the house he had bought

in Tavistock Square in London.

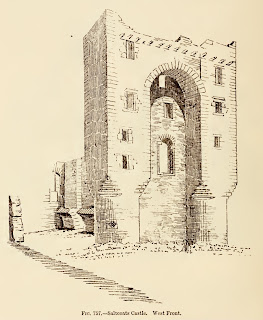

In

May 1911, the Great Lafayette arrived in Edinburgh with his troupe for a run of

shows at the Empire Theatre in Edinburgh.

However, he wasn’t in Edinburgh long before disaster struck. On the 2nd of May his beloved dog

died suddenly. Lafayette was heartbroken

and had to have the best for Beauty, even in her death. He had her embalmed and was given permission

to have her buried at Piershill Cemetery, by the company that owned it. This was under the provision that on his death

he too would be buried in the same plot as his dog. Even though he was completely heartbroken by

Beauty’s death, Lafayette being the consummate professional carried on with the

run of shows, all of which were sold out.

On

the night of the 9 May 1911, The Great Lafayette’s act was all going as planned

and the audience were enthralled. They

had watched as he shook out a large square of silk and dropped it to the

ground, then whisked it away to reveal a Teddy Bear sitting there. He made as if he was winding the bear up and

it then came to life, danced around, and conducted the theatre orchestra before

toddling off stage. He had juggled with

goldfish, produced two children out of a piece of cardboard and imitated

various conductors of bands. The finale

had then been ‘The Lion’s Bride.’ Just

as that had reached its conclusion and Lafayette and the other performers were

taking their bows an electrical fault on stage caused the scenery to catch

fire. The audience at first assumed this

was part of the act, until the manager had the fire curtain dropped and asked

the orchestra to play the National Anthem.

This, and the fact that smoke was now pouring out into the theatre

encouraged them to leave. Remarkably

they all escaped safely. Things on the

stage, behind the fire curtain, did not go so well. The lion, which was terrified by the flames,

was running loose and because of this no one could get past it to one of the

fire exits. Other performers were

trapped by the flames from the burning scenery, and all was a scene of

confusion. It appears that Lafayette may

have escaped from the flames at first, but on hearing of the situation with the

lion had run back to try and save it. This

time he did not make it back out.

The

theatre burned for three hours before the flames were brought under control. The next day several bodies were recovered,

and the newspapers made much of the body of Alice Dale being found. She was the little person who had played the

Teddy Bear and her charred remains were found still in the bear costume. The body of the Great Lafayette was then

found on the stage, though only it wasn’t actually his body, but rather that of

his body double for several of his acts.

At the time no-one realised this and the body was cremated, and

arrangements made to inter the ashes at Piershill Cemetery. But a couple of days later another body was

recovered under the rubble and this one wore an array of rings that were

identified as those the Great Lafayette had worn. Realising their error, this body was then

cremated, and the urns switched to make sure the right remains went to

Piershill. In total eleven people died in

the fire, all either performers or stagehands.

On

the 14th of May 1911, the Great Lafayette’s funeral took place. Despite it being a misty, damp day, huge

crowds turned out to watch the funeral cortege of twenty carriages make its way

through Edinburgh and down to the cemetery.

The cortege was led by the hearse containing Lafayette’s remains. It was drawn by four ‘Belgian horses’ with

‘nodding black plumes on their heads.’ At

the cemetery, the urn containing Lafayette’s ashes was placed in Beauty’s

coffin between the paws of the dog. A

graveside service was then held before the coffin was lowered into the ground

and the Great Lafayette was laid to rest.

Lafayette

left his vast fortune to his brother who promptly took the money and left the

country without paying off the debts accrued by Lafayette, and also without

paying the funeral costs. This resulted in a court case from which we learn

that the total cost of the funerals for both Beauty and the Great Lafayette was

£411. In today’s money that would be

about £48,700. Probably not to bad for a

showbiz funeral.

In

2011 the Festival Theatre, which stands on the site of the old Empire Theatre,

held a series of events to mark 100 years since the fire and the death of

Lafayette and the other performers.

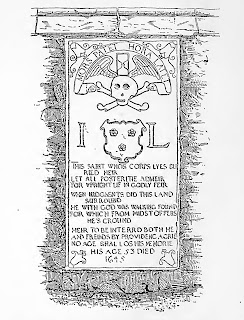

I

left the Skulferatu that accompanied me on today’s walk in the flower trough by

The Great Lafayette and Beauty’s grave.

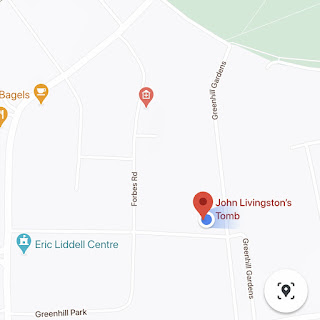

The coordinates for the location of the

Skulferatu are:

Latitude 55.955495

Longitude -3.138674

I

used the following sources for the tale of The Great Lafayette –

Newspapers –

The Evening News, London – May

10, 1911

The Globe, May 10, 1911

The Westminster Gazette – May

10, 1911

The Scotsman – May 11, 1911. May 13, 1911. May 15 1911.

Strabane Weekly News – May 20,

1911

Sunderland Daily Echo – May

11, 1911

The Courier – May 22, 1913

Wikipedia – Sigmund Neuberger

The Edinburgh Reporter

The

Edinburgh Reporter - The Great Lafayette Festival 9 May 2011

Article and

photographs are copyright of © Kevin Nosferatu, unless otherwise specified.