Morton Castle is not the easiest place to find, which despite being a pain in the arse, actually adds to its charm and also to a sense of it being in a more remote and undiscovered location. On our trip there our Sat Nav took us to a row of houses and told us we had reached our destination. We were in fact still a couple of kilometres away, and it wasn’t until driving a bit further on and having checked the various map apps on our phones that we managed to find where we wanted to go. A narrow, winding, single track road then led us to a small parking area. From there it was a short walk down the path of the Morton Heritage and Nature Trail to the ruins of the castle.

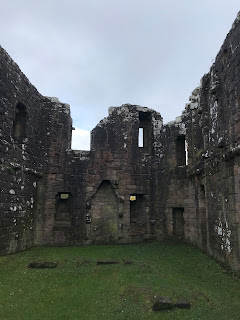

The ruins of Morton Castle stand on the south

west slopes of the Lowther Hills and overlook Morton Loch. The castle was originally a two storeyed hall

block with a four storey turreted gatehouse at the west end of the building and

an angle tower at the east end. The

lower storey of the building would have consisted of a kitchen, a storage area,

and a lower hall, while the first floor would have housed the great hall. The private chambers of the lord of the

castle and his family would have been in the tower at the east of the building.

The site on which the castle sits is

thought to have been where a stronghold was built by Dunegal, Lord of Nithsdale

in the Twelfth Century. These lands were

later granted to Thomas Randolph, the nephew of King Robert I. The castle itself is believed to have been

built in the early Fourteenth Century and was mentioned in 1357 in a treaty

with England to release King David II from captivity. The treaty called for the demolition of

several castles in South West Scotland, Morton Castle being one of them. It is unclear how much of the castle was demolished

at that time.

In 1372 the castle and the lands around

it were passed through marriage to the Douglas family, who later became Earls

of Morton. It is believed that parts of the

castle were rebuilt in the early Fifteenth Century. The castle was then leased out to another

branch of the Douglas family, though does not seem to have been their primary

residence and may have been used mainly as a hunting lodge. It appears that it later fell into disuse and

by 1714 was abandoned. Much of the stone

was then taken away and used for constructing farm buildings. The castle was acquired by the Duke of

Queensberry and was later passed down to the Dukes of Buccleuch. It then passed into state care under a

guardianship agreement in 1975.

I left the Skulferatu that accompanied

me on my trip in a crack in one of the outside walls of the castle.

The coordinates for the location of the Skulferatu

are –

Latitude 55.274466

Longitude -3.747266

I used the following sources for information on Morton Castle –

Historic Environment

Scotland – Statement of Significance Morton Castle

Morton Castle Statement

of Significance

Canmore – Morton Castle

Information Boards at

Site

The Castellated and

Domestic Architecture of Scotland from the Twelfth to the Eighteenth Century

By David MacGibbon and

Thomas Ross

1886