The

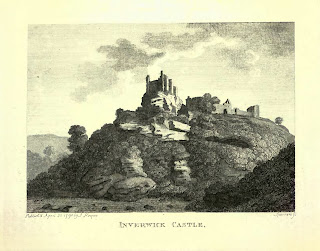

ruins of Innerwick Castle sit on a sandstone outcrop, above a steep, rocky

ravine that drops down through Thornton Glen, to the shallow waters of Thornton

burn. On the other side of the glen once

stood Thornton Castle, of which nothing now remains. Whether there was some

strategic importance to the castles being so close together I don’t know,

though they were near to the Great North Road that ran from London to Edinburgh,

so maybe they were some sort of strongholds against the English army, that occasionally

marched up that way to carry out an invasion or get up to some mischief

making.

Built

in the 14th Century, Innerwick Castle was once the stronghold of the

Hamilton family, and the history of the castle, like that of many castles, is

bloody and violent. It fell into the

hands of the English after their success at the battle of Homildon Hill in 1402. Then, in 1406, it was besieged by the army of

the Scottish nobleman, Robert Stewart, and was recaptured and destroyed. A few years later it was rebuilt and appears

to have enjoyed a period of prosperity when it was extended several times.

This

period of peace and prosperity ended in the mid-16th Century when Scotland

and England became involved in a series of vicious and violent confrontations,

known as the ‘Rough Wooing’. During this

time the English forces carried out a series of attacks and invasions into

Scotland, in an attempt to compel the Scottish Parliament to confirm the terms

of the Treaty of Greenwich. This treaty,

which had been agreed by Henry VIII of England and James Hamilton, the Regent

of Scotland, included a proposal that Mary, Queen of Scots, and Henry’s son

Edward should wed when they were of age.

However, the Scottish Parliament had rejected the treaty, much to Henry’s

displeasure. In 1547, Henry was dead, and his young son

was King, though the real power lay with his Protector, Edward Seymour, the Duke

of Somerset. And Seymour, being an

ambitious sort, decided it was time to get the treaty sorted, so he led an army

into Scotland.

On the 6th of September 1547, a unit of English hakbutters (men armed

with an early form of musket) besieged Innerwick Castle. The castle was

defended by the Master of Hamilton and eight other men. They barricaded the doors, blocked up the

stairs and defended from the castle battlements. However, the hakbutters blasted

away at them with their guns, and managed to force their way into the vaults

below. There they piled up straw and wood and set the castle ablaze. Blinded and suffocated by the smoke, those

defending the castle cried out for mercy, but the hakbutters burst through the

doors onto the battlements and shot dead eight of them on the spot. The ninth, who saw what fate had befallen his

comrades, jumped from the castle battlements in a desperate effort to save

himself, falling 70 feet down the ravine and into the river below. Miraculously, he survived and on seeing this,

the hakbutters above in the castle, allowed him to escape. Unfortunately for the poor man, he ran towards

nearby Thornton Castle, unaware that it too was being attacked by English

troops. On being spotted by them he was ‘slain’. Shortly after his death, Thornton Castle also

fell into the hands of the English troops who blew it up with gunpowder.

Though

much of Innerwick Castle was badly damaged by the attack in 1547, parts of it

must have been habitable, as in the 1650s the Covenanters used it as one of

their bases from which they harassed and attacked Oliver Cromwell’s troops. Later, in the 1820s, the castle was home to a

local man called Sandy Cowe. Living

there on his own, he grew garden plants in parts of the castle and on its

grounds, which he sold around the county.

The ruins of Innerwick Castle have been an inspiration for many artists from the amateur to the well-known. In 1831, J.M.W. Turner was invited up to Edinburgh to meet up with Sir Walter Scott and his publisher, to discuss his illustrating of Scott’s Poetical Works. On his way up, after a stop off at Berwick upon Tweed, he spent a couple of days in East Lothian sketching some of the ruined castles there. One of these castles being Innerwick. The series of sketches he drew are now held by the Tate.

The

land in which the castle sits in is now a nature reserve owned by the Scottish

Wildlife Trust. A steep, narrow, earth

trodden path leads up to it, and it was up this path that I trudged on a fine,

still day. Ignoring the sign warning of

the dangers of loose masonry, I made my way inside the castle and wandered

through what remained of the vaults and once grand rooms. I took in the views over Thornton Glen and

then after my wanderings, left the Skulferatu that had accompanied me, in a gap

in the wall of a swirling tower where a stairwell to the upper levels had once

stood.

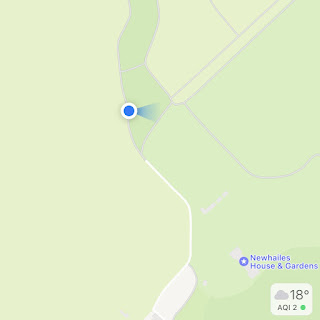

The

coordinates for the location of the Skulferatu are –

Latitude

55.955625

Longitude

-2.425939

what3words:

aimlessly.stealthier.superhero

I used the following sources for information on Innerwick Castle –