Newcastle

has always been a part of my life. I

used to have a lot of family down there, so visited often. I still like to head down two or three times

a year and have a wander around.

For

those unfamiliar with the city of Newcastle, it sits on the north bank of the

River Tyne in the north east of England and is considered to be the capital of

the area. It grew up, around and over the

Roman settlement of Pons Aellius, flourished and expanded during the fourteenth

century as an important site in the wool trade, and then played an important

role in the UK’s coal industry. With the

decline of its docks and the coal industry the city suffered like many other

northern towns and cities, though through various regeneration projects it now

has a diverse and thriving economy.

When

I’m in Newcastle, one of the walks I like to do takes me over the High level

Bridge, a double decker bridge with a railway running over the upper

level. From this bridge there are amazing

views over the River Tyne to the iconic Tyne Bridge and several other bridges

across the river. There are also great

views of the riverside areas of Newcastle and Gateshead.

The

view over Newcastle from the bridge always reminds me of a story Grandpa Nosferatu

told me, probably because it is not that far from the area where he once lived. Grandpa Nosferatu was born and brought up in

the slums of Newcastle in the early part of the Twentieth Century, and as a

young boy he lived with his family in a dingy, cramped house in the terraces by

the docks.

My Grandpa’s father was a brute of a

man who ruled his family with extreme violence. A man who terrorised his wife

and children and expected them to obey his every word. Basically, he was a big, nasty, aggressive

bully. As a kid Grandpa Nosferatu had

learnt quickly that you never went against what his father said, or there would

be dire consequences. One of the many

rules and stipulations that his father had was that his children never played

in the docks. However, this was one rule Grandpa Nosferatu couldn’t help

breaking, there was just too much fun to be had down there. The place was a playground heaven for kids, what

with all the boxes to climb, reels of rope, and various bits of junk lying

around that just cried out to be played with.

One evening, a six or seven year old

Grandpa Nosferatu headed down to the docks to meet some friends, climb boxes

and play at being sailors. However, his friends never turned up. This did not

deter my grandpa, who sat on top of one of the many boxes pretending that it

was his ship, and he was the captain. He was suddenly disturbed out of his play

by the noise of an argument. He shimmied down from the box and sneaked round to

see what was going on. From a safe vantage point, he saw three men. Two were

arguing with the third. As the argument

escalated the two men began to push and punch the third man. Then one of the

men pulled out a knife and stabbed the third man several times. He collapsed, lifeless, to the ground. For a while the two other men seemed at a loss

as what to do. After some discussion they

dragged the third man’s body to the edge of the dock and rolled him over into

the swirling, dark waters of the Tyne.

They then hurried away, looking nervously around as they went. My grandpa ducked down and hid for what felt

like hours, too terrified to move in case the men came back and saw him. Eventually, when he had plucked up enough

courage, he left. For a while he walked

the streets in shock and facing a huge dilemma, did he go and tell the police

what he'd seen and risk the wrath of his father, or did he keep quiet? The

thought of his father being in a rage was so terrifying that he decided to keep

quiet about what he had seen and for many years he never told a soul about the

murder he witnessed at the docks. And he

really only ever told the story to highlight just how scared he had been of his

father. A fear that drove him to walk

out of the family home at the age of fourteen and never return.

Anyway, back to the bridge. The High Level Bridge was commissioned in 1845 and Robert Stephenson, the renowned engineer and son of the famous inventor George Stephenson, came up with the design for it. The stipulations he was given for the bridge were that it was to carry a railway, roadway, and a pedestrian walkway. In order to avoid having to build a very wide and very expensive bridge, he designed it to be on two levels. The lower level consisted of a road and two walkways, one on either side of the road, while the upper level carried the railway. Work then began on the construction of the bridge with houses on each side of the river being demolished. Piles were then driven into the riverbed; the approach viaducts were constructed and the ironwork was cast and put in place. In total over 5,050 tons of iron were used in the building of the bridge and around 1.5 million bricks. The cost of its construction, including the costs of building the approaches to the bridge and compensation to the families whose houses had to be demolished to make way for it, was estimated to be around £491,000, which translates in today’s money as being around £46 million.

The

bridge was opened in 1849 by Queen Victoria and was considered to be ‘one of

the finest pieces of architectural ironwork in the world.’

Over

the years, the High Level Bridge has undergone several renovations and upgrades

to ensure its continued use and safety. In 2008, the bridge was refurbished at

a cost of £40 million, which included strengthening work and the replacement of

several components.

Today,

in the howling wind, I walked over the bridge and took in the views. I then left the Skulferatu that had

accompanied me on my walk in a ledge in the ironwork, high above the Tyne.

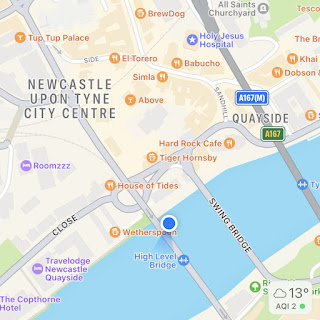

The

coordinates for the location of the Skulferatu are –

Latitude

54.967402

Longitude

-1.609099

what3words:

fact.grab.hotel

I

used the following sources for information on the High Level Bridge –

Tourist Info at Site

Network Rail – The

History of the High Level Bridge, Newcastle