It was one of those warm, winter days, when the sun is out, and you feel that spring might come early. A good day for a walk. Having recently come across some maps of walks around Gore Glen, by Gorebridge, I decided to follow one and have a nice woodland walk. So, I took a train from Edinburgh to Gorebridge and set out. However, my map reading skills and sense of direction are so bad that I ended up doing a bizarre route that took me to the back of some sewage works and then on to a path that looked like it had been made by deer rather than people, which led up a steep embankment and into some grounds I probably wasn’t meant to be in. Finally I ended up back in Gorebridge and then back on the proper path again. I followed this and ended up in the woods where I came across the ruins of the Stobsmill Gunpowder Works.

I wandered around the crumbling remains of

the buildings that once housed a thriving and somewhat dangerous industry. The stone walls were being subsumed back into

nature and were moss covered with ferns growing from the gaps and cracks. Birds sang in the trees above and water bubbled

in the nearby stream. It was all very

different a couple of hundred years ago when there would have been dozens of

men at work in and around the buildings, and water wheels would have been churning

away to power the whole operation.

In 1794 the works at Stobsmill were

constructed for the Hitchener and Hunter Company to start producing

gunpowder. You might think that this was

a company well versed in the production of such an explosive material, but no,

it was the venture of William Hitchener, a millwright, and John Hunter, a

farmer. They were both originally from

Surrey and had applied there for a licence to produce gunpowder but had been

turned down as they lacked the necessary skills or experience to run such a

dangerous business. Somehow, they had found their way to Gorebridge where,

along with a more experienced partner, John Merrick, they applied for and were

successful in gaining a licence to manufacture gunpowder.

The works were constructed in an

isolated area within the shelter of a valley near to Gorebridge. The valley was used as a natural barrier in

case an explosion occurred, and artificial mounds were created and planted with

trees to lessen any explosion that might happen. The works were built by the Gore Water, with

the river being channelled and used to drive the ten waterwheels that powered

them.

The gunpowder produced at the works was

exported all around the world and was used by the British Army during the

Napoleonic Wars.

As you might expect in an era when

health and safety concerns were minimal, there were quite a few accidents at

the works and several large explosions.

In 1803 an explosion occurred that killed John Hunter, who was in his

garden when a large stone from the blast tore off his arm. Two of the men working at the mill were also

killed in that explosion.

On the morning of 18 February 1825 an

explosion occurred that was so big it could be heard in Fife, and it rattled

the windows of those living in Edinburgh, eight miles away. It was also reported that the shockwave from

the explosion caused the church bells in Dalkeith, some five miles away, to

start ringing and that a ploughman working in a field almost a mile away was

thrown thirty yards by the force of the blast.

Luckily, he was unharmed. While

in the nearby village of Gorebridge the windows of all the houses were blown

in.

Shortly before the explosion, two of the

workmen at the mill, Richard Cornwall and Walter Thomson, had been busy loading

casks of gunpowder from the ‘Drying Room’ on to a horse drawn waggon. The casks were then to be taken to a store in

another building a short distance away.

Cornwall, at some point went back into the ‘Drying Room’ to retrieve

more casks, while Thomson was loading them on to the waggon. Something then triggered a huge explosion in

the ‘Drying Room’, which in turn also caused the store to explode. These buildings were completely destroyed and

both Cornwall and Thomson were blown to pieces.

A report at the time describes how the mangled fragments of the men’s

bodies were found scattered around over the distance of a mile and that it was

impossible to tell which of the fragments belonged to which man. Other workers on the site were reported to

have been blown to the ground, with some throwing themselves into the river in

search of safety. While the body of the

horse that had been with the waggon was found thirty yards from the explosion

and the trees all around were shattered and broken. Some passers-by, who had been on the high

road at the time of the explosion described a huge column of black smoke rising

up from the valley and large stones being thrown up from it, like a volcano.

It was reckoned that about 60 barrels of

gunpowder had exploded, each of these containing 112 lbs (51 kg) of powder. So

in total over 3000kg of gunpowder. You

would think that given an explosion of that enormity the mills might close

down, but no, given a business that lucrative and that vital to war, Empire,

etc., they carried on. Then in 1827

there was another explosion…

On Saturday 29 September 1827 at around seven

thirty in the morning the residents of Gorebridge were woken by a loud blast when

the ‘Corning House’ (the building in which the powder was separated into

granules) at the gunpowder works exploded.

The horrific scene that met those who hurried to the ruined building to

help was described graphically in a report of the incident by the Caledonian

Mercury –

‘…the three men who were employed in the

premises at the time…were killed by the explosion. One of the unfortunate men had his legs torn

from his body; another his belly torn open, and his entrails hanging out; and

the third was blown into the water at a considerable distance from the Mill,

where he was found dead about an hour after.

Search was immediately made for the members which were severed from the

bodies: but when found, they were so dreadfully mutilated, that it was

impossible to know to which the different members belonged. When looking around the scene of this

terrible visitation, it seemed as if some destroying angel had been there,

doing his work of desolation and death. The

premises wherein the explosion took place…lay in one heap of ruins; the

surrounding trees were stript of their foliage; and the grass was burnt black

and bare…’

Now, you may be thinking that given the

amount of accidents at Stobsmill, those working there were a bit careless, or

that the owners were unduly lax over health and safety, and uncaring when it

came to their workforce. However, it

seems that explosions at gunpowder factories were not that uncommon, that they

were just one of the dangers of working in that trade. A few days after the explosion at Stobsmill, there

was an explosion at the premises of Messrs Pigou & co, a Powder Mill in

Dartford, Kent. Three workmen were also

killed in that explosion.

Anyway, the buildings at Stobsmill were

repaired and work carried on. Then on

Wednesday 21 March 1838, at around six thirty in the morning there was another

explosion. The working day had begun

around half an hour earlier and the workforce was spread out throughout the

site engaged in their various tasks. In

the ‘Corning House’ two men, Robertson, and West, were busy at work when there

was a huge blast that destroyed the building.

Their colleagues ran to the smoking ruins and in the rubble they found Robertson. He was still breathing but died shortly after

from his wounds. The body of West was

then found ‘at some distance’ from the building. A report of the incident in The Scotsman

notes that the damage to the buildings and machinery was significant and that ‘the

loss to the proprietor must be considerable – insurance on property of this nature

being of course out of the question.’ No

shit Sherlock!

Again the buildings were repaired, and

work carried on until around 1861 when the mills finally closed. Now all that is left of them are the ruins in

the woodland of the Gore Glen. A place

so peaceful that it is hard to imagine that it was once a site of heavy

industry and several tragic, fatal, and devastating accidents.

I left the Skulferatu that had

accompanied me on my walk in a moss and lichen covered hollow in one of the

walls.

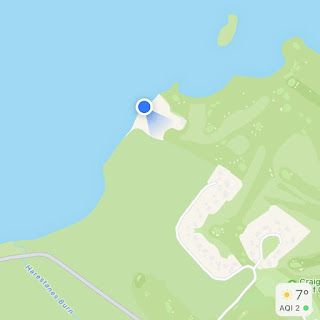

The coordinates for the location of the Skulferatu

are –

Latitude 55.83960

Longitude -3.051440

I used the following sources for

information on Stobsmill Gunpowder Works -

The Statistical Accounts

of Scotland 1791-1845, Vol 1

Temple, County of

Edinburgh (Page 53)

Gorebridge Community

Development Trust

https://gorebridge.org.uk/heritage/stobsmill-gunpowder-works-an-introduction/

The Scots Magazine

Tuesday, 1 March 1825

Caledonian Mercury

Saturday, 19 February

1825

Caledonian Mercury

Monday, 1 October 1827

The Scotsman

Wednesday, 28 March 1838

Article and photographs are copyright of © Kevin Nosferatu, unless otherwise specified.