When

I go cycling from Edinburgh to North Berwick, I like to take the coastal road

and enjoy the scenic route. Just before

I reach Gullane, I turn off from the road and take the bumpy path along the

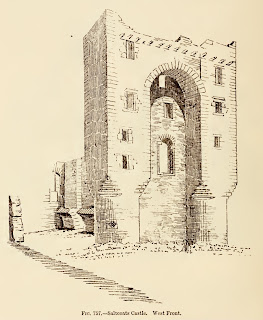

John Muir Way and cut down to the rather spectacular ruin of Saltcoats

Castle. On a sunny day it’s relaxing

just to sit in the castle grounds, rehydrate and take in the great view.

The

history of this rather marvellous ruin starts with a legend of daring and

bravery, or the needless slaughter of a wild animal, depending on your point of

view. The story goes something like

this…

…back

in the mists of time, when the lands that now make up East Lothian were sparsely

populated and thick with forest and wild beasts, there was a huge, wild boar

that terrorised the area. This beast was enraged by anybody it saw on

its territory and had chased, gouged and maimed a dozen or so people. Soon it got to the stage where those in the

villages were terrified of travelling to market, the peasants working the

fields were terrified as they worked, the landlords in their stately homes were

terrified of walking outside in their gardens and those travelling from

Edinburgh towards England took a long route round to avoid the

area. The King, on learning what was

going on, offered a large reward to anyone who could kill the boar and rid the

land of its menace. Many tried and died

in their attempts. The boar always

seemed to be one step ahead of them and ambushed many a brave hunter, slicing

through their weak and mortal bodies with sharp tusks that seemed to be made of

steel. Soon the boar was being seen as

more than just a beast, it was a demon sent from Hell or a punishment from

God. The churches rang out their bells

and the holy prayed in hope that the good Lord would end their torment. But he didn’t.

Then

along came a young man from the Livington family. His family had fallen on hard times and he

had decided that to improve their lot he would take on the challenge of killing

the boar. First of all, he set about

preparing for the task and had a special glove made of thick leather. The inside of this glove was heavily padded

with down. He also had a steel helmet,

body armour and a sword made for the task.

Expensive though this was, he persuaded the craftsmen who made the

pieces for him that he would pay them when he had killed the boar. Such was his self confidence in completing

this task that they all agreed to this and he was soon ready to go on the hunt

for the deadly beast.

On

a summer’s morning young Livington set off out into the forest. As he went, he would call out every so often

in order to attract the boar. However,

it was almost as if the beast could sense him and his purpose, and for hours

Livington walked without seeing any sign of it.

Growing weary from walking, Livington stopped near a stream and drank

from it. He sat by it for a while and decided

to give up for the day and to start his hunt again the next morning. As he rose to make his way back out of the forest,

he heard something crashing through the undergrowth. It drew nearer and nearer. Livington drew his sword and readied himself. With a roar the boar burst through the

undergrowth to where Livington stood.

The creature was huge with tusks like sabres and eyes that glowed red

like the hot coals of a fire. For a

moment it stood still staring at Livington, then it stamped at the ground, snarled,

and rushed at him with tusks out. Like a

matador, Livington spun to the side and the boar charged past. It came to a skidding halt and turned again

to face him. It’s eyes burning with

anger and hate it let out a roar and charged at him. Livington once more sidestepped the boar as it reached

him, howling with frustrated rage it turned and came at him again. As it was almost on top of him Livington

thrust his gloved arm down into its mouth.

The shock of this caused the beast to stumble and fall, taking both it

and Livington to the ground. The beast,

unable to move its head enough to gouge Livington with its tusks, kicked out at

him, catching him several times about the body and denting the armour he wore. In this onslaught Livington almost lost grip

of his sword, but just managing to keep hold of it he thrust it up and through the

beast’s heart. The beast let out a

groan, almost human, then sighing it died by Livington’s side. Exhausted, Livington lay by it and prayed a

prayer of thanks to the Almighty Lord above.

A

group of five woodsmen, had bravely ventured that day into the forest to chop

wood, and had heard the commotion.

Cautiously they approached to see what was going on and saw Livington

lying beside the body of the boar. Thinking

that he must have died in the fight, they went over to offer prayers for him. On seeing that he was alive and suffering

from no fatal wounds, they helped the exhausted man to his feet. They then cut and stripped a large branch and

tied the body of the boar to this. Four

of the woodsmen carried it out, while one carried Livington on his

shoulders. As they walked out through

the forest, they came across a den of

six squealing little piglets. The six little piglets mama boar had been

protecting from those who encroached on her territory. These were gathered up, placed in a sack, and

handed to Livington.

On

hearing that the boar was dead, villagers from all around came out in

celebration. That night Livington and

the villagers, from landlord to peasant, all feasted on suckling pig and wild

boar sausages, black pudding, and roast pork.

All washed down with local ales and fine wines imported from afar.

A

few days later the King heard that the boar had been killed. For Livington’s act of bravery and ridding

the land of the terrible beast the King granted him the lands from Gullane

Point to North Berwick Law. It was on the

land acquired by Livington, near to Gullane, that Saltcoats Castle was built.

Up

until the 1790s the helmet said to be worn by Livington when he slayed the boar

hung in the church at Dirleton in East Lothian.

When the church was being repaired the helmet was removed for

safekeeping and was lost.

At

the mouth of the Peffer there is a small stream that goes by the name of

Livington’s Ford. It is here that

Livington supposedly slew the wild boar.

Anyway,

let’s get back to the castle…the name of Saltcoats Castle is thought to come

from the fact that it stands on ground that was in ancient times a salt

marsh. The castle is a Sixteenth Century

courtyard castle that rose to a height of three storeys. It was enclosed by a wall and in the grounds,

there would have been an extensive garden and orchard. There was also at one time a bowling green to

the east of the castle, though all signs of this have been lost as it has been

ploughed over numerous times and become part of the surrounding fields.

The

castle was built in around 1590 for Patrick Livington and his wife Margaret

Fettis of Fawside. In the early 1700s the

castle and estate were acquired by the Hamilton family when James Hamilton of

Pencaitland married ‘the heiress of Saltcoats’, Margaret Menzies. The castle was inhabited until around the

late 1790s, the last tenant being a Mrs Carmichael, who died there. It was then left uninhabited for several

years. Around 1810 much of the stonework

was removed to build farm steadings and walls.

The ruined cottage which stands at the side of the castle was built

around this time and on its front wall there is a panel taken from the castle with

the coat of arms of Patrick Livington carved into it.

Saltcoats

Castle has now been designated as a scheduled monument.

The

Skulferatu that accompanied me today was left on a ledge above the keyhole

window on the tower.

The coordinates for the location of the

Skulferatu are:

Latitude 56.026982

Longitude -2.827307

I

used the following sources for information on the castle –

The Castellated and Domestic Architecture of Scotland from

the Twelfth to the Eighteenth Century

Volume Four

By David MacGibbon and Thomas Ross

1887

Lamp of Lothian or the History

of Haddington form the earliest times to 1844

by James Miller

1900

St Baldred of the Bass and Other Poems

By James Miller

Oliver and Boyd

1824

Wikipedia – Saltcoats Castle

Canmore – Saltcoats Castle

Canmore

- Saltcoats Castle, Gullane

Article and

photographs are copyright of © Kevin Nosferatu, unless otherwise specified.